Using Reinforcement Learning to Train Ants

Completed:

AntsRL - Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning

If you ever observed a colony of ants, you may have noticed how well organised they seem. In order to gather food and defend itself from threats, an average anthill of 250,000 individuals has to cooperate and self-organise. By the use of specific roles and of a powerful tool - the pheromones - thousands of somewhat limited ants can cooperate to achieve greater goals.

We were interested in exploring the emergence of such behaviors in a simulated environment. Giving some “ants” the correct tools to use and an environment to explore, would we see these kind of phenomena appear from nothing?

At cross-roads of Multi-Agent Theory and Reinforcement Learning, we designed a system that would let a colony of very simple ants develop clever strategies to optimize their food supply.

Important note: throughout this post, we will sometimes use words that suggest agents have an internal mental life, intentions, free-will, etc. It is only to make explanations easier to read and absolutely does not reflect the reality of things. No more than a few thousand numbers govern our agents’ behaviors, which forbids any teleological interpretation. Come on, it’s just matrix multiplications.

Delving into the problem at hand

First, let’s cover the main hypothesis we assumed to perform our experiment. It is essential to know from where we start in order to assess the beauty of any eventual emerging behavior: we would not like to be spellbound at something not that surprising, right?

Hypotheses

The first and most important hypothesis is the total isolation of agents. It is one of the main hypothesis of the multi-agent paradigm: agents don’t have any direct way of communication that doesn’t pass through the environment itself. Therefore, any communication mean is subject to the unexpected, and therefore fallible. In other words, we took a special care to not let agents communicate with each-other in a hive way, transmitting direct information between them. The only way they can communicate is by depositing pheromones behind their back, and watching around them for other ants and traces of previously dropped.

The second hypothesis is the relativity of perceptions. It is important that our agents doesn’t have any clue what is their location and their orientation in the world. In a general way, they only see the world from their individual perspective.

The Environment

As for any RL application, the definition of the environment is at the core of the project.

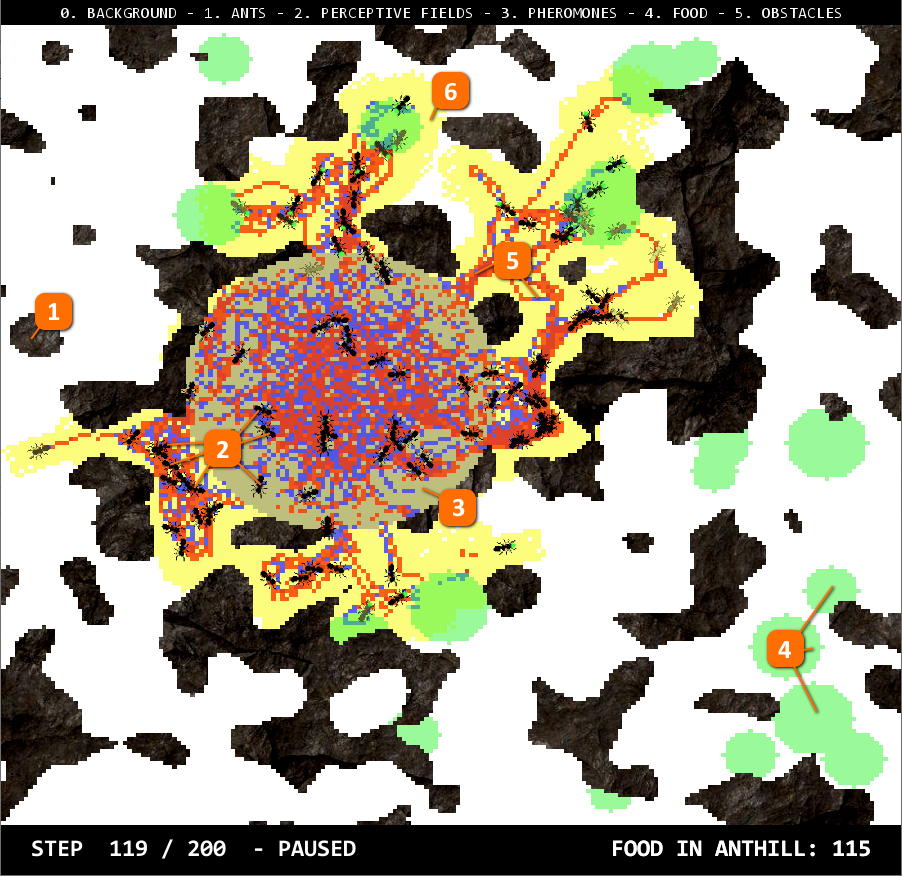

- The walls: those are proceduraly generated rocks that forbids the ants to move through.

- The ants: our agents’ representation are these little black ants.

- The anthill: the blue circle in the center is the anthill from where every ants comes and where every ants have to bring food back.

- The food: those green circles, also proceduraly generated, are food sources. Ants can pick them up, which removes a pixel, and then drop it into the anthill.

- The pheromones: we gave two types of pheromones to our ants. A red one and a blue one. Both of them are deposited by the ant below itself, and slowly fade away as tie goes by.

- The exploration map: completely invisible to our ants, this yellow visualization represents the region of the map that was explored by the all colony.

The code to generate an environment is made as simple as possible so that anyone can experiment with different map configurations. By using different procedural generators, one can generate walls with various densities, a lot or a few food sources, away or not from the anthill, etc. Finally, a seed can be specified to make sure that the generated environment is controlled if necessary, which is useful to evaluate our different agents on the same map.

generator = EnvironmentGenerator(w=200,

h=200,

n_ants=n_ants,

n_pheromones=2,

n_rocks=0,

food_generator=CirclesGenerator(n_circles=20,

min_radius=5,

max_radius=10),

walls_generator=PerlinGenerator(scale=22.0,

density=0.1),

max_steps=steps,

seed=181654)

Finally, the environment is a continuous 2D space, even though walls, food, anthill and pheromones are on a discrete 2D grid. Ants are moving with floating points coordinates and rotations, which allows for more precise movement. The map also warps to the other side upon reaching the edges. The ants don’t see any of this: when they look at an edge of the map, they simply see the other side of it. When they move through the edge, the are warped on the other side too.

On the technical side, note that visualization is completely separated from simulation. We can simulate the environment with ants inside it without visualizing anything, which is much faster, and then record a run in a file. Afterwards, we can visualize any recorded run, changing replay speed and choosing what to see. Save files are quite heavy though.

The Agents

You already saw them in the picture above, but let’s give some more details about our agents: the ants. As explained in the hypotheses, our agents are completely independent from each other and don’t share any direct information. Their internal definition vary with the different models we implemented, but their perception of the world and their ways of acting on it remain the same.

You can see when an ant has picked up some food: it has a green dot between its mandibles. Isn’t it cute?

Perception

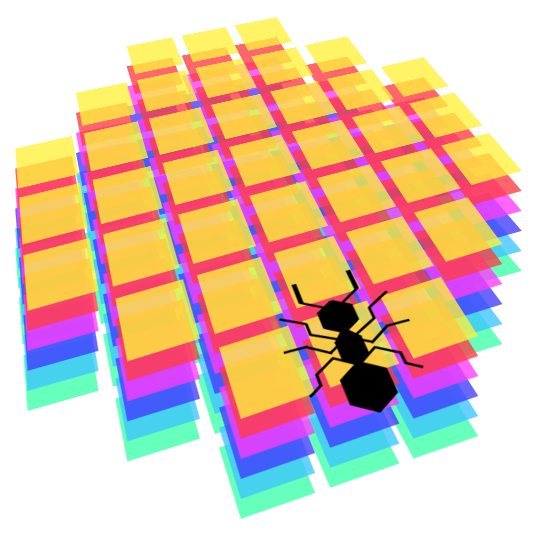

They see in front of them in a certain radius. Here is an image representing the shape of their perception, in terms of discrete slots in the 2D grid. First, we compute the floating point coordinates of every perceived slot, by applying translation and rotation relative to their current position, then we round those coordinates to obtain the real 2D grid slots they perceive. It sometime gives weird results, but we consider that our ants are like real ants: very bad at seeing things! They should however be able to easily detect pheromones in front of them, walls, food or other ants.

In mathematical terms, their perception is always a square matrix of 7x7, with a mask to make it more round, and with as many layers as necessary to represent every ‘channel’ of their vision. In our case, each type of object in the world (anthill, other ants, food, walls, pheromones, etc.) is represented on a different layer of perception. This gives very regular perception which is easy to feed to a neural network afterwards.

Actions

Ants have four types of actions they can perform:

- Move ahead/backward

- Turn around

- Grab/release their mandibles (picking up food or dropping it)

- Deposit pheromones of chosen type

For the sake of simplicity, we decided to automate actions 1 and 3: ants always move forward at a speed of 1 slot per simulation step. They automatically pick up food when their mandibles are empty and there is food on the floor, and they drop it if they are in the anthill. We could have let them learn those actions too, but we thought there was nothing really complicated in these simple rules so we saved some learning time and implemented them manually.

In the end, our ants have to handle their heading to go in the right direction and to drop pheromones to communicate with other ants in the long term. This is, as we will see, already quite difficult.

Multi-Agent

But our ants are not alone. Here we defined a single one of them, but they are between 10 and 100 ants in the simulations we performed. Of course, everyone of them works the exact same way, even though we introduced some individual differences at some point. This common structure actually allows us to treat all ants at the same time in a batch. It is not only a neural-network kind of batch, it is also very useful at simulation stage as an ant is not an instance of a class, but rather a line in a big array. Upon performing an action, we apply the individual actions of each ant all at once on the big array. For example, to move every ant forward in their own direction, we add $\cos(\theta)\cdot x+\sin(\theta)\cdot y$ to the original $x, y$ coordinates array. Every operation is always applied on all ants, which doesn’t forbids to take individual actions, but which avoids a lot of useless loops.

Matrix operations become quite complicated when it comes to individual perception fields, parallelized over every ant. But it’s working.

How to motivate the ants

At this stage, we have functional, but completely empty shells of ants. Now comes the time to give them life and make them actually perform actions. We will begin with very dumb ants, implementing our first model: RandomAgent.

Beautifully random, this behavior doesn’t do much but we can already see what the ants can do. Note that this has been sped up by 4. We can see the ants wandering and dropping blue and red pheromones everywhere. Also, as they automatically pick up the food they walk on, and drop it in the anthill if they happen to walk inside it again, the score in the bottom right keeps growing (note that a small bug makes it start at a given number, but we will just not consider it). This fixes the baseline for our next experiments: as you will see, we will first lose a lot of points, but then our ants will manage to do much better than random.

If you’ve heard of reinforcement learning before, you know that one of the key elements to learn an optimal strategy is to have a well designed reward function. This is how we will teach our agents to perform certain kinds of behaviors. Here, our ants only have one goal: relentlessly supply the anthill with food. This simple task requires long-term planning and social cooperation. Hence, we divided it in a set of different sub-goals: smaller rewards that we will use to tell to our ants “yes, you did great, continue like this!”.

A reward to explore

Since the food sources can spawn quite far from the anthill (we also have a specific map generator that forbids those circles to appear too close from the anthill), ants need to explore the map. However, since they don’t have the GPS included, they have no clue where they are located. They must find a way to move forward, without getting stuck on walls, and without going back where an ant was before. We denote this reward $r_{explore}$ and compute it every step. For each new grid cell an ant discovers, we give it one point. But as ants have no way to know if a cell was visited by another ant before, they have to use their pheromones to mark their path.

A reward to pick up food

It is a very simple reward that gives one point to any ant walking into some food and picking it up. As pick up is automatic in our setting, it just pushes the ants to be attracted by food when they see it. But more generally, it gives them an incentive to find tasty salad as fast as they can! We denote this reward $r_{food}$.

A reward to go back home

Just like a night with too much alcohol and no battery in the phone, our ants have a lot of trouble finding their way home. They need a little help, but we didn’t give them one directly: we designed a reward that gave them one good point whenever they reduced the distance between their position and the anthill once they carry some food. As always, ants cannot perceive the rewards, they have to find ways to earn it more efficiently by using the tools at their disposal.

With this incentive to go back home after picking up some food, we began to see behaviors using pheromones to trace their way back! We denote this reward $r_{anthill-heading}$.

A reward to drop the food

The final reward, the most important of all. After their long journey through the lands, it is time to drop the food in Mount Doom the anthill. Each time an ant reaches the anthill carrying some food, it is dropped and the ant gets one point. We denote this reward $r_{anthill}$. Note that in the evaluation, we only grade our model using this reward, as we don’t really care how much of the map was explored or how much food was picked up if it wasn’t dropped in the anthill afterwards.

One reward to rule them all

If you followed everything from here, you should understand that those sub-goals should not have the same importance. For example, exploring should be just a prerequisite before actually bringing food back to the anthill. If an ant has to choose between picking up food and exploring the map a bit more, it should a priori go for the food. How can we specify that in our training ?

One simple way is actually to give a higher or smaller weight to the reward depending of the task achieved. We write our final reward function :

\[R = \omega_1 \cdot r_{food} + \omega_2 \cdot r_{explore} + \omega_3 \cdot r_{heading-anthill} + \omega_4 \cdot r_{anthill}\]where $\omega_1$, $\omega_2$, $\omega_3$, $\omega_4$ are arbitrary factors that are set at the beginning of the training. Those are hyper-parameters that we had to tune with great care as they completely change the way our ants learn and behave.

Teaching the ants with DDQN

DDQ… what ?

The goal of this post is not to explain in detail what is the deep Q-learning algorithm (“DQN”; Mnih et al. 2015). If you are not familiar with this, we invite you to read this great post which explains everything you need to know about reinforcement learning!

However, if we had to summarize it briefly, let’s say we have a model that tries to estimate what is called the $Q$-value of every world state $s$ for each possible action $a$. The $Q$-value represents how interesting a given state or action is, in terms of a future reward. We call $Q$-value function the function that uses learned parameters $\theta$ to try and estimate the $Q$-values. We will denote it $Q(s, a, \theta)$.

In our case, the $Q$-value function will be a neural network which takes as input the observation of the world made by the ant, and outputs a value for each possible action. DQN improves and stabilizes the training of our $Q$-learning by two innovative mechanisms: replay memory and periodically updated target.

The replay memory is exactly what its name says: a big table containing previous courses of actions taken by some ants in a given state, with the rewards obtained on the next round. After each training step, we save $e_t = (S_t,A_t,R_t,S_{t+1})$ in this table, with $S$ the states, $A$ the actions and $R$ the rewards. When updating our neural network, we can then draw random batches and use them as training data. Experience replay improves data efficiency, removes biased correlations in the observation sequences and smooths out changes in the data distribution.

The second improvement uses two separate neural network. We train the main one every step, but we use a copy called target network to decide on which actions to take at each step. The target network is only replaced by a new copy of the main network once in a while. It makes training more stable and prevents short-term oscillations.

Multi-action Q learning

So, we have a way to estimate the Q-value for different values of an action given a state. However, in our case, we have not one, but two different sets of actions. Ants can choose their direction and which pheromone to use, if any.

So we want our neural net to output Q-value for each action. How to do that ? The paper Branching Q-learning A. Tavakoli, 2019, gives a shared decision module followed by several network branches, one for each action dimension. In the end, we have two separate network heads predicting $Q$-values for independent actions. To decide the actions to perform, we only have to select the greatest value of each branch, which gives us a combination of actions!

Teaching a simple task: exploration

Since we didn’t have a way to be sure that we were going in the right direction (well, it had to work theoretically, but that’s easy to say), we decided to take a first peak at a simpler problem: teach the ants to explore the map.

We set $\omega_1 = 1$ and $\omega_2 = \omega_3 = \omega_4 = 0$, launched a training for 50 epochs with 20 ants. Here are the results!

This replay was taken from a random map on evaluation mode. From this replay, we can get two major insights:

- Agents learned to go where there is no pheromone because it is more likely to be a portion of the map that is not explored yet.

- Agents learned to use the two pheromones in a interesting way. They use the red one upon exploring, and the blue one when they pass through already seen territory. What does that mean? We don’t know. But maybe they do.

Great, our model works! However, let’s try and be more like rigorous scientists and prove you that our ants improved by displaying the graph of the mean reward and mean loss per episode of training:

An increasing loss? Well, that is not that bad in reinforcement learning. In our case, it is mainly increasing because the rewards our agents get are getting higher and higher, we also increases the range of the errors the network makes upon predicting those $Q$-values. What we’re really interested in is the blue curve where we can clearly see the exploration increasing from the random baseline (which is already quite good at exploration only).

Agents with memory

We successfully trained an exploration agent. Now, let’s take a deep breath and dive deep into the real task: make the ants pick up food and bring it back to the anthill. We start training using our full reward function $R = \omega_1 \cdot r_{food} + \omega_2 \cdot r_{explore} + \omega_3 \cdot r_{anthill-heading} + \omega_4 \cdot r_{anthill}$ with the following parameters:

- $\omega_1 = 1$

- $\omega_2 = 5$

- $\omega_3 = 1$

- $\omega_4 = 100$

However, this gave us mixed result. Ants tends to get stuck in areas of food without ever leaving them. We though this could be because the ants have no information of their previous states and actions, and might be struggling following a strategy on the long term.

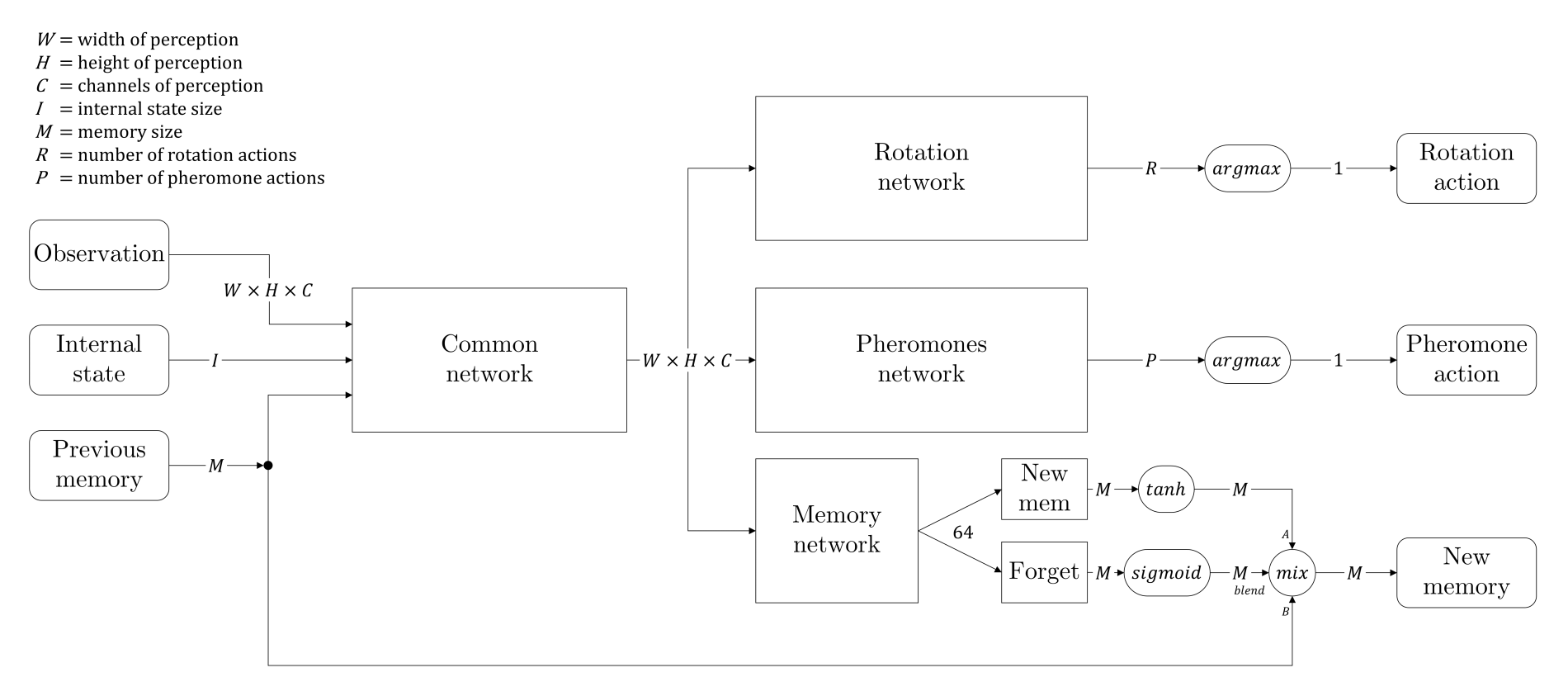

We decided therefore to change the architecture of our network, and took an inspiration from LSTM networks. We added a branch to create some kind of memory information that would be passed from the current state to the next one. In addition, we added a forget gate, which is a stack of layers followed by a sigmoid activation, so that the network could learn when to remember, and what to remember. The complete architecture is given by the diagram below.

We call “internal state” two pieces of information that are not directly visible in the perception matrix: how much food the ant is currently holding, and a random seed which gives every ant the opportunity to differentiate itself (the seed remains the same for a given ant during all the episode).

Finally, the memory is stored in the replay memory as any observation information, giving each ant the ability to be trained to remember things correctly.

Training time !

Now that we have a stronger network, a good reward function, we just need to start heating the machine and start training! But wait… There is still some important hyper-parameters to choose.

The number of ants The good thing with this kind of multi-agent system is that we can make it work with any number of ants However, since training with an army of 250,000 ants like in real life doesn’t seem reasonable for the planet -and our poor computers-, we decided to train with only 20 ants. Note that until a certain number of ants, the cost of simulating more of them is very low! This is the main advantage of putting all of them in a big array.

The number of epochs This parameter is chosen empirically. Because the environment is coded in Python, the engine is quite slow. We therefore had to limit the number of epochs to 150-200 to limit training time. This is quite a small number of episodes if we compare to other reinforcement learning application. However, results showed it was sufficient to get interesting behaviors in our case.

Decaying epsilon Exploration is key in reinforcement learning. We used a decaying $\epsilon$ factor using this formula : \(\epsilon = max(\epsilon_{min}, min(\epsilon_{max}, 1 - log(\frac{episode + 1}{15})))\)

where $\epsilon_{min} = [0.01, 0.1]$ and $\epsilon_{max}=1$. This allows our agents to explore a lot during the first episodes, and then slowly start to pick the best action.

Results

Finally, it’s time to see some results! Did our ants learn anything? Can we give an interpretation to what has been learned? We will cover this kind of questions from now on.

Final results on a long run

Even though we trained our colonies on not more than 2,000 steps for each episode, we made a video of one colony for 20,000 steps to see what was happening. And remember how we trained our model with 20 ants? Well, once trained, we can actually use any number of ants we want! So, because it’s more fun, we ran this simulation with 50 ants. We can finally see our ants gather all the food in the map, relentlessly building their pheromone network throughout the map, changing target as soon as one is exhausted… We included some pheromones-only parts as we find them beautiful.

What we observe is that they build some kind of network of pheromone that they use to move around the map. Because they learned to be attracted by a certain type of pheromones, they tend to favor some paths more than others. This creates a hierarchy of paths, with some being real highways, and some others being more like small country lanes.

So, is it actually like real ants?

No, it’s not.

But… we can see very interesting behaviors here. Actually, the most interesting part cannot be seen in the videos because it happens during training. Among the different things our agent learns, some are directly related to the environment and others are kind of social conventions, or put in other words, group strategies. For example, the use of pheromones is a convention that every ant follows (because they have the exact same brain in our project), but that has no particular meaning in the environment.

During training, we see different conventions emerge, and then disappear to let a new one take place. What you see in the last videos is just one of the ways our ants used the pheromones to share information. As these conventions are not rooted into the environment in any way, they can evolve and disappear quite easily. What makes a convention remain is simply its tendency to bring better rewards to individual ants.

But it’s not that simple. Our hypothesis to explain what we saw (and better exploit it in the future) is that two main factors influence the appearance and disappearance of such conventions.

First, the exploration $\epsilon$, as it allows ants to act randomly a certain percent of the time, if implemented naively (sampling at each step for all ants), tends to let those conventions disappear as $\epsilon$ of the time, all ants refuse to follow it.

Secondly, we believe that those conventions take some time to emerge as they do not directly profit to the individual depositing the pheromones. The common agent has to learn that by performing some actions, other instances of it will increase their rewards. From the neural network perspective, it basically requires the replay memory to come to a point where the rewards from some samples depend on the actions, which is the main principle of discount factor $\gamma$. It turns out to be the same problem as long-term planning in Reinforcement Learning, which Q-Value learning doesn’t completely solve.

Considering those insights, we believe that two important things to do in order to obtain more clever social conventions is to decrease $\epsilon$ at some point, which we did, and to allow for more and simpler communication between agents. Here, the pheromones are systematically let behind the ant, which implies by design that it is a long-term action. Maybe a more direct form of communication - antenna-to-antenna - would allow for better social conventions.

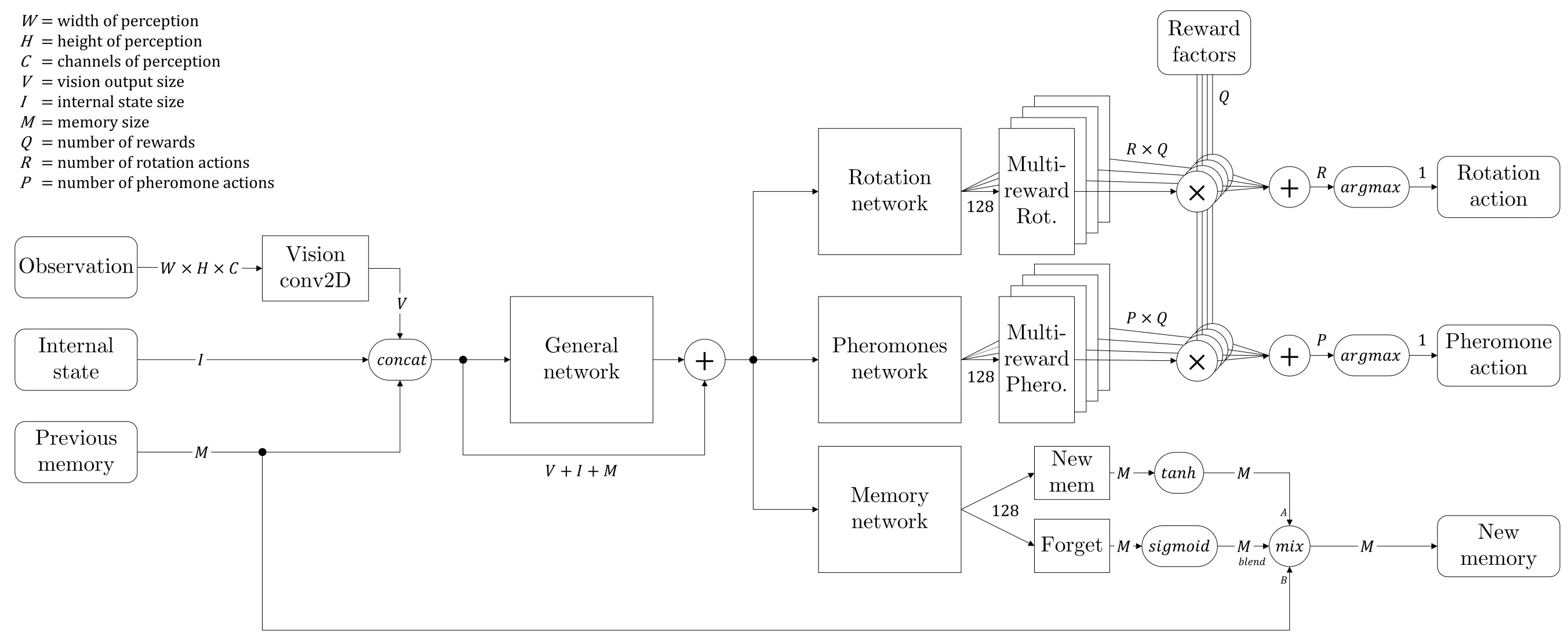

Unfinished business: multi-reward network

As mentioned previously, we split our network in two branches to predict the rewards of two separate sets of actions. However, we ask those branches to predict one reward per action, regardless of the composition of this reward in multiple factors (exploration, food pick up, heading to anthill and finally dropping the food into the anthill). As we give arbitrary weights to these individual rewards, sometimes one of them can completely shadow the others when it is first discovered by the agents, giving a hard time to the neural network as it has to be precise at different orders of magnitude at the same time.

We then made an attempt that makes the network more complex, as shown in the image above, letting it predict as many different reward values for each possible action, before multiplication by weights: each part of the network had to predict an independent type of reward, and it’s only by performing the weighted sum of these individual Q-values that we obtained the actual max-policy action of the agent. We remembered not only the global reward in the replay memory, but each individual value, allowing the training to specify to each network’s part its corresponding target.

The two main advantages of this method are:

- The network has to predict values in a controlled and uniform range, not a single value that can vary of several orders of magnitude but still needs precision at lowest ones. Here, each part can specialize in a specific reward, potentially giving contradictory results which are ruled out afterwards when summing Q-values.

- Once the agent is trained, we can vary the weights dynamically, obtaining different ant behaviors very easily. Although it is quite artificial as we are the ones deciding this, it allows for a nice experiment where each ant has a unique ‘personality’, resulting in more diversity into the colony without having to change the common network: they all have the same brain, but not the same motivations.

Sadly, we didn’t have enough time to find a working set of hyper-parameters. As this method is more complex, it is subject to more randomness in the learning and we had a hard time making it produce interesting results. From the theoretical point of view, there is also no guarantee that Q-value learning still holds when multiple and contradictory rewards are trained on the same agents, but on the other hand, we don’t see reasons why it shouldn’t work. We will update this blog-post as soon as we get it working! For now, everything is working perfectly, but training is not giving results as good as before.

Conclusion, open questions and further developments

Our initial objective was a little ambitious: we were already imagining colonies fighting with each other for food, ants pushing rocks out of pathways or into small rivers to get through obstacles and obtain more food… Always aim for the stars!

The results, even after 150 epochs, are very promising and we definitely saw some emerging behavior in the ants society, which was our main concern. Now, we feel like we can’t stop there, but it’s already the end of the time we had for this project. However that won’t keep us from updating this project and this post!

We even implemented movable rocks at first, that ants could push. Depending on the weights of such rocks and on the number of ants pushing (average direction), they moved more or less quicker. But it was a little bit buggy, putting some ants inside walls and such filthy things. We decided not to include them in the demonstrations.

In further developments, we would let the ants act on their mandibles in order to choose between picking food up and fighting threats like other ants. We would also make the maps more complex and offer the ants a way to communicate more easily through a visible state that other ants can see when close enough. But before all of that, we would re-implement our simulation in C++: we have a scoop, Python is slow.

We only saw the very beginning of what we expected as emerging behaviors, but we believe that if we add more tools at the disposal of our agents, and more complex problems to solve, we would see more and more clever behaviors appear!

Well… A lot of things can be done, starting from where we stopped! Maybe a new chapter will follow? Who knows. Be prepared.

Links & References

To get the full Python source-code of the project, please visit our github: https://github.com/WeazelDev/AntsRL

References:

- “DQN”; Mnih et al. 2015

- A (Long) Peek into Reinforcement Learning (blogpost)

- Branching Q-learning, A. Tavakoli, 2019

- Reinforcement Learning, an Introduction - R. Sutton

- Deep Reinforcement Learning for Swarm Systems, M.Hüttenrauch 2019

The main modules we used throughout our project:

- Numpy - for simulation

- PyTorch - for agent definition and DQN training

- PyGame - for visualization